How to do an architecture interview

Many software engineering interview loops include an “architecture interview”, where the candidate is asked to develop a high-level design for a software system. Over the last few years, I’ve given many, many of these interviews, so I’ve seen a wide range of performances across the spectrum, from “absolutely terrible” to “we need to hire this person now!”.

Based on these experiences, I’d like to share what it takes to succeed in these interviews as the candidate, and some common behaviors to avoid.

How it works

Although the exact format can vary, most architecture interviews begin with an open-ended prompt of the form “design X”. The X can be filled in with a generic software system, for instance:

- A distributed key/value store

- A web crawler

- A video streaming system

An alternative, which I think is the more interesting approach, is to fill in the blank with a well-known product or product feature; some examples here include:

- Generating the Facebook news feed

- Executing a Robinhood user’s trade flow

- Matching Uber drivers and riders

The target design, whether generic or product-based, might be something related to the company’s own systems or products, but it’s often not.

The question is left open-ended and high-level deliberately. The interviewer is not looking for a specific answer (usually), but rather wants to observe the process by which you break down the problem, dig into the pieces, and justify your decisions. As you discuss your solution, the interviewer will ask questions, steer you towards or away from specific areas, and really try to understand what it would be like to collaborate with you on the design of a real project.

Structure is key

Because the questions are so open-ended, and because you’re being evaluated as much on your process as your specific solution, structuring your answer is really, really important. Here’s a structure that I think works well for most of these questions.

Step 1: Clarification

Once you get the question, the first step is to make sure you understand what you’re being asked to design. For the “design a system to match Uber drivers and riders” example, for instance, if you’ve never used Uber before it’s probably good to say that and ask for more details. Even if you’re familiar with the thing being asked about, it’s helpful to draw a simple picture with stick figures to make sure that you and the interviewer are on the same page.

This is also the time to ask about rough orders of magnitude scale (e.g., how many requests per second are expected, etc.). However, I wouldn’t get too bogged down in these numbers- a good design should have lots of room for growth and not be built to a specific set of static dimensions.

Step 2: High-level drawing

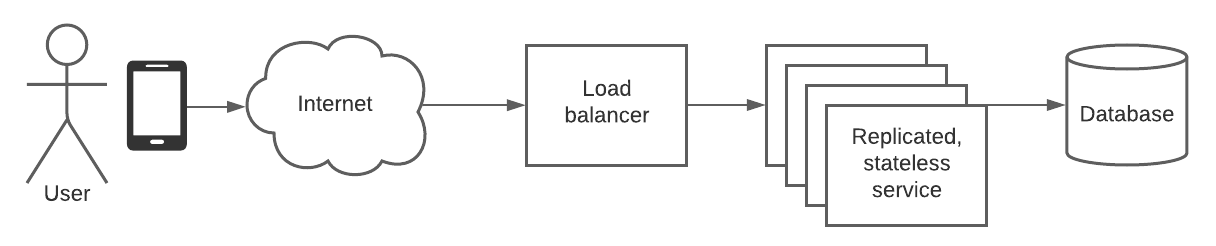

Next, you should draw out a high-level diagram that shows the major pieces and how they’re connected. As discussed later on, the idea here is to be high-level and not over-engineer at this phase. You should mention that you’re deliberately being simple and high-level, and that you’ll dig into improvements later so the interview knows that you’re not being sloppy.

In the Uber case, as in many others, you’ll probably have clients, a layer of web servers, and some sort of storage layer that keeps track of the states of the users and other entities in the system.

Step 3: Interface details

Once you have a picture of the main pieces, I think it’s really useful to describe the system interface, i.e. what are the specific inputs and outputs, independent of any internal implementation details. In the case of a client/server type design (most common), these map to the requests that the clients make and the responses that they get.

Being really specific about these (the different types, what they include, etc.) ensures that you and the interviewer are on the same page and also guides the discussion of the implementation details in later steps.

In the Uber example, you’ll have requests from the rider client (i.e., app) for a ride, requests from the driver client to change status, to accept a potential ride or not, etc. In this specific example, the request flows can be fairly complex and are probably an important part of the design.

Step 4: Implementation details

Once you’ve defined the high-level pieces and the interfaces, it’s time to dig into the internal implementation details. There are many different things you could focus on here, so it’s really important to lean on your interviewer for guidance. Some potential topics to cover here include:

- Tradeoffs in choices around specific components (e.g., using a relational DB vs. a NoSQL solution)

- How a specific request type is handled end-to-end (including DB changes, etc.)

- Schemas for any data stores

Step 5: Enhancements for scalability, performance, etc.

Once your interface and basic implementation are in place, you can then discuss how to increase the maximum load that your system can handle. This is also a good time to talk about the reliability of your design and what you could do to improve it, if applicable.

As with the previous step, it’s really important to lean on your interviewer here and try to dig into the areas that they feel are the most interesting to cover.

Although the exact solutions will vary based on the context, some general approaches that may be helpful here include:

- Replication: Stateless components can be replicated to handle more traffic and be resilient to failures in individual instances. This may also help for stateful things like DBs if you send the reads and writes to different instances and can hand-wave away consistency issues.

- Sharding: Splitting up your traffic by geography, user id, etc. and allocating each bucket to a semi-independent copy of your system may allow you to increase scale without redesigning everything from scratch.

- Caching: Adding caches in front of read-only data can significantly improve performance in many cases and reduce DB load.

- Queueing: Adding queues in your system may improve reliability and shield downstream components from load spikes. However, it can increase latency and also is hard to implement in synchronous request flows, so it’s most appropriate for asynchronous data pipelines.

Common mistakes

Even with good structure, there are some very common traps that candidates fall into that reduce the quality of their answers in my view.

Being too service-oriented

Service-oriented-architecture (SOA) is a design pattern which eschews monolithic components for more specialized, distributed ones. Over time, it’s evolved into the idea of breaking up monolithic systems into lots of tiny microservices.

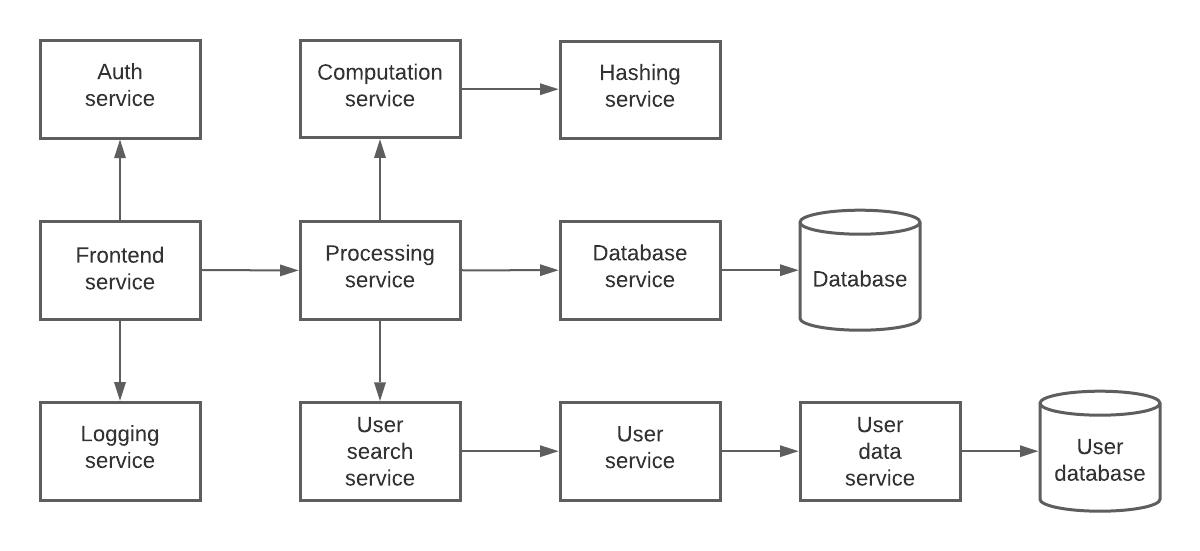

So, for instance, instead of having a single server that both accepts requests from clients and updates the DB, you might introduce a “database service” between the app server and the database. Now, you have two services instead of one. Over time, the original app server is split out further and further until it’s just a router without any business logic in it.

While SOA and its microservices variant have benefits in some cases, they’re super easy to abuse, make designs significantly more complex, and, without more understanding of the motivations, might not be necessary in a real-world, large-scale system at all.

Here’s an extreme example of what I don’t want to see:

Err on the side of being monolithic, then split things out later in the interview if and only if there’s a good reason to do so.

Over-engineering too early

Related to SOA abuse is over-engineering your solution too early in the process. Yes, having 3 layers of caching, or a queue between your app servers and your DB, or a fancy sharded data store might make your system more scalable. However, it’s unlikely that you’ll need those in the first iteration, they make your design significantly more complex, and, without more testing and iteration, it’s impossible to know how much these things will actually help.

As mentioned earlier, start simple and then add complexity later in your answer if needed. Adding complexity is easier than removing it, and this also matches how many real-world systems are implemented.

Using components you don’t fully understand

Don’t include overly-hyped technologies in your solution (“Kafka!”, “Cassandra!”, “machine learning!”) unless you really understand them and have day-to-day experience using them. Otherwise, you’re likely to use them in the wrong way or look like an idiot when the interviewer asks you follow-ups about how they work.

It’s much better to stick to less-sexy things that you actually know, e.g. MySQL, which can still be (and actually are) the basis for many real-world, large scale systems. In the course of your answer, it’s fine to mention other technologies that might be relevant, but you should explain that you don’t have a lot of experience with them so you’d need to do more investigation before including them in your design.

Getting specific in the wrong areas

It’s impossible to cover all of the details of a complex system like Uber’s ride matching in a 45-60 minute interview. When you focus too much on one specific thing (e.g., the database schema), you’re necessarily omitting the chance to cover other aspects of the problem in a very detailed way.

As mentioned earlier, start at a high-level and then dig into the lower-level components that your interviewer steers you towards. Don’t waste time on details that your interviewer doesn’t care about.

Conclusion

Doing well in an architecture interview is prerequisite for many software positions, particularly the higher-level ones. Having a solid structure, starting from a high-level, avoiding over-engineering, and sticking to what you know are the keys to success.