Tech employee retention is a serious issue

A lot of companies, both in tech and other industries, are having trouble retaining employees at the moment. The so-called “great resignation” of 2021 has gotten a lot of newfound press coverage, but in reality these resignation waves are nothing new in tech; in an industry where companies can rise and fall quickly and where employees can easily move between jobs, individual companies will often have retention problems even if the broader economy does not.

In this post, I want to describe the various resignation waves that I’ve seen in my career thus far and what companies can do to respond to them.

When retention is a problem

Even the best companies under the most auspicious circumstances will have some voluntary turnover. It’s just natural that in any given year, a small percentage of otherwise happy employees will want to retire, go back to school, move to a smaller company, or pursue some other opportunity that requires them to quit their jobs.

Companies build this kind of steady, predictable turnover into their hiring plans, and it generally doesn’t cause problems. New people come in to the replace the ones who leave, and the refresh rate is slow enough that it doesn’t disrupt operations or affect morale.

Sometimes, however, internal or external circumstances can disrupt this balance, causing the rate of people voluntarily leaving to go beyond a comfortable threshold. This has a number of negative effects inside the company, including:

- People leave faster than they can be replaced. The workload on the remaining people goes up significantly and team plans need to be trimmed because of staffing shortages.

- The people leaving have special skills and knowledge that has been built up over their time at the company. Even if their positions are backfilled quickly, it takes a long time for the new people to become as productive as those they’re replacing.

- People lose colleagues who they enjoyed working with and made them motivated to stay.

The big problem here is that many of these things form amplifying feedback loops. As more and more good people leave, the burden on the remaining employees becomes higher and they themselves become more likely to quit, which just makes the retention problems worse.

I’ve personally observed various degrees of these resignation spirals at a few points in my career; some examples include:

- At Google in 2010/11: Facebook and others started aggressively poaching employees so they could build their own variants of Google’s technologies and products. This didn’t affect the teams I worked with at the time, but it apparently was causing a lot of specialized talent in certain areas (e.g., data center hardware and web search) to leave.

- At Twitter in 2015: User growth came to a standstill, and the stock started tanking. Many employees received a significant fraction of their compensation in equity, which meant their pay decreased a lot. At the same time, various executives were also quitting or being forced out, which made the company seem rudderless and further lowered morale.

- At Segment (my current employer) this year: The “great resignation” is happening and, moreover, some are feeling post-acquisition malaise (we were acquired by Twilio last year) and want to return to smaller companies.

The wrong response

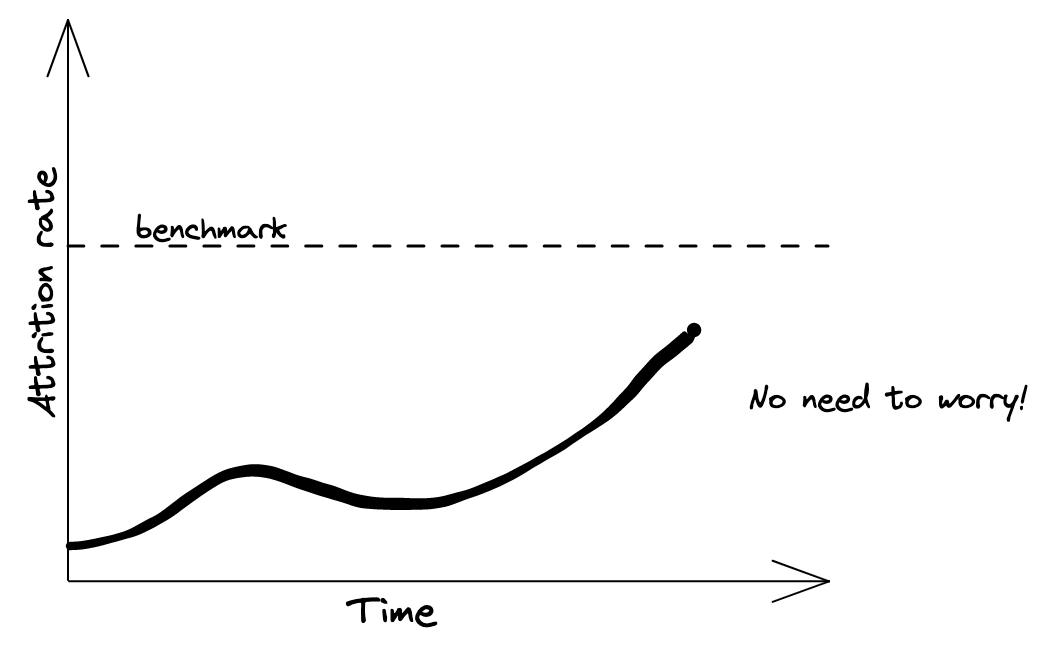

Companies are continually monitoring internal data on employee departures and comparing their numbers to industry benchmarks. The most common response I’ve seen from company leadership when attrition numbers creep up is to dismiss them as not a serious concern as long as the company average stays under some pre-determined threshold, e.g. 20% per year. Even if employees start noticing that more and more of their colleagues are leaving and start raising concerns, it’s easiest to say “we’re ok because we’re well below X%” (whatever the threshold is).

This type of response is frustrating for so many reasons.

First, attrition isn’t going to be uniform across a company with hundreds or thousands of employees. It’s highly likely that certain classes of people (e.g., senior engineers or people in a particular division) are quitting at a higher rate than the average value. Within these groups, localized resignation feedback loops can form before they show up in a company average.

Second, attrition is a trailing metric. The number only reflects the final outcome (employees leaving), which may happen many months after people become unhappy and start to look for new jobs. Half of the company could be in the process of leaving, but you won’t see that in the attrition numbers until they’re gone.

Third, it takes a while for any mitigation to take effect. Increasing salaries or giving people more equity, for instance, may take months (because of board approval, budgeting processes, etc.). The same applies for non-pay-related improvements like easier internal transfers, improved benefits, or more vacation time. If employees are already in the process of looking elsewhere and have momentum in that process, the promise of a pay raise or some other benefit six months down the road might be too late to have any effect.

What to do instead

Respond early

The key to keeping retention problems under control is to respond to them before the feedback loops described above can take hold. If attrition is low but steadily increasing, this is a sign of a serious problem that, at the very least, needs to be acknowledged and investigated.

As described above, it can take many months, even in the best run companies, for mitigations to be approved, rolled out, and felt by employees. Acting early allows for the latter to happen before the resignation wave crests, thus reducing its peak height.

Aggressively adjust pay

Increasing pay is a key lever for increasing retention and making people more reluctant to quit. Unfortunately, many larger companies have rigid schedules and procedures around pay adjustments, e.g. only considering merit increases once a year or only allocating a fixed budget (say, 3% per employee per year on average) for these increases.

If employees can get large raises by switching jobs now, but have to wait 6 months for the potential of maybe getting a pay bump that’s just slightly larger than inflation, they’re probably going to start exploring their options now.

While it may be hard to completely rework compensation update cycles on short notice, motivated companies can and should do out-of-band pay increases, either via one-time bonuses, new equity grants, or updates in base pay. Ideally, these are applied widely across the company and not just to a select few who are particularly at risk of leaving.

The best example I saw of this was at Google. The CEO got up at an all-hands meeting at the end of 2010 and announced that everyone was getting a 10% pay increase effective January 1 of the next year (only a few weeks away). Moreover, the bonus structure was being changed so that much of it would now be folded into base pay instead of being a discretionary, once-a-year payment.

The end result was that my biweekly paychecks and those of my colleagues in product and engineering increased by about 25% without any of us having to lift a finger. I didn’t have access to the numbers at that time, but I would guess that this aggressive pay bump reduced attrition and also increased the acceptance rates on new offers.

Consider non-pay-based strategies too

Pay isn’t everything, and many employees could still be unhappy and quit even if their pay is increased. A few other, non-pay-related things that can make a difference include:

- Easier internal transfers: A lot of people quit their jobs because they want to do something new. If they can do this easily inside the company, without requiring multiple rounds of interviews and other bureaucratic red tape that external candidates have to go through, then this might be seen as an easier path than switching companies.

- More time off: Giving people more vacation time, either officially or off-the-book, can increase happiness a lot without requiring any pay adjustments.

- Better benefits: For US-based employees, options like $0 premium health insurance and access to mega backdoor Roth transfers can be strong factors in keeping employees where they are, particularly when compared to smaller companies that often don’t have these.

Don’t wait for people to give notice

Some companies are willing to aggressively improve pay or working conditions, but only if employees come to them with offers from other companies, i.e. effectively threaten to quit. While this may reduce attrition a bit, the incentive here is to be continually interviewing elsewhere; this is not only a huge time suck for employees but also provides lots of opportunities for competing employers to woo these interviewees and entice them to switch jobs before the original employer can counter.

Ideally, good employees in a tight market are rewarded with regular, market-aligned pay increases without requiring external interviews or threats to quit. This reduces stress on both sides and decreases the incentives for otherwise happy employees to dip their feet in the water and explore other opportunities.

Conclusion

Retention among employees is a serious issue that tech companies should be continuously monitoring and responding to. Keeping good employees from leaving is way, way cheaper and less disruptive than having a wave of departures followed by a months-long process of recruiting new people, hiring them, onboarding them, and giving time for them to ramp up. This is always true, but especially so in a tight job market like the one that we’re experiencing now.