Service meshes are hard

I’ve worked on deploying “service meshes” at multiple companies. Although they look great on paper, deploying them is a huge pain, with a high risk of serious production outages. In this post, I want to share some of my war stories and caution against diving into the service mesh hype too quickly.

Aside: What’s a service mesh?

A common pattern in software engineering is to support a product or feature via multiple, semi-independent components. This blog, for instance, is hosted in Github Pages. When your browser requests the HTML for this page, your request most likely hits some sort of frontend proxy (e.g., Nginx), which then sends the request to a backend server (implemented in Ruby, perhaps), which then sends out requests to even more services, e.g. to record stats or fetch user information.

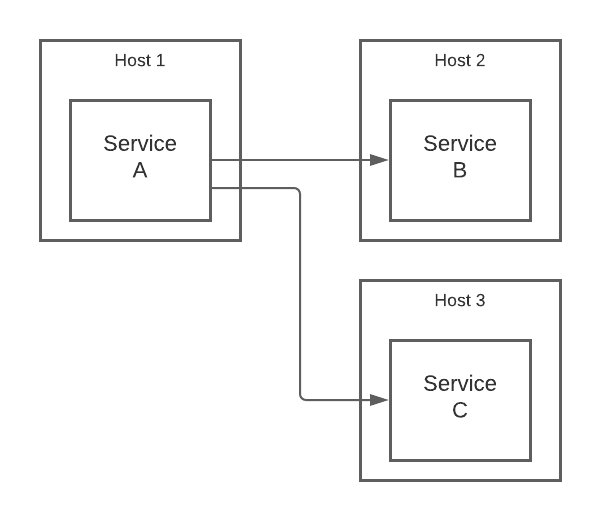

Direct communication

The simplest approach for handling requests between these components is to have them communicate directly. Here’s an illustration:

Each arrow represents a request from a client to a server. These requests are typically implemented with HTTP, but might use a specialized, binary protocol instead, e.g. when using something like Apache Thrift. The underlying bytes can be encrypted but are often not since this would require the clients and servers to handle protocols like TLS, which adds complexity and reduces performance.

The picture above doesn’t show how service A “discovers” the addresses of B and C. These might be hard-coded, looked up in DNS, or fetched from a centralized service registry like Consul. The important thing to note, though, is that the details of doing this are handled by A itself.

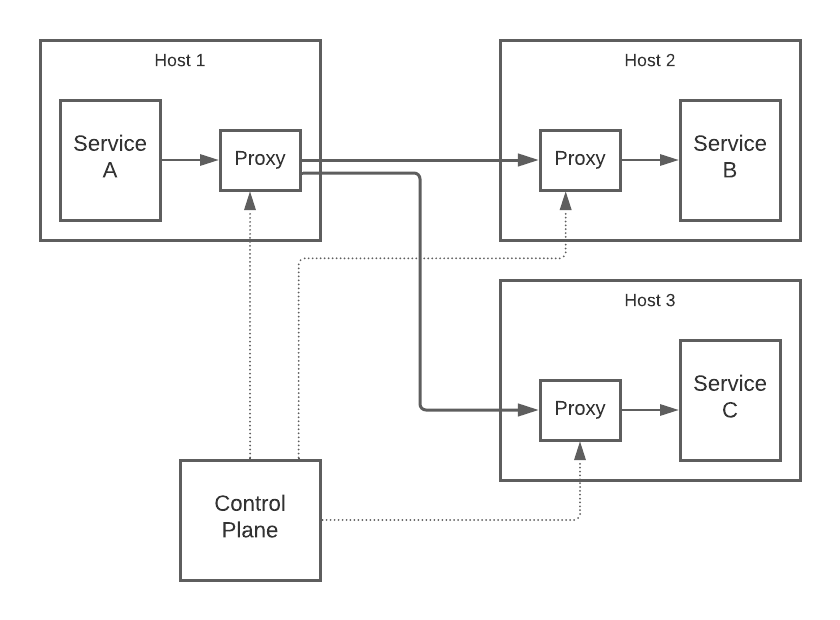

Using a service mesh

A service mesh is a dedicated infrastructure layer for handling the details of this inter-service communication. Although the exact architecture varies, with a mesh the picture above might become:

Now, service A doesn’t communicate directly with B and C. Instead, it sends requests to a local (outbound) proxy that then sends the requests to the (inbound) proxies for B and C. The latter then forward the requests to the service instances on their respective hosts. The links between proxies can be, and often are, encrypted via mTLS.

The control plane is needed so that the proxy configurations can stay up-to-date. If host 2 disappears, for instance, and is replaced with host 2a, then all of the proxies on the hosts talking to B need to be updated with the new address.

Benefits

The nice thing about the mesh architecture is that your services no longer need to handle the low-level details of communicating with others. This makes a lot of things substantially easier, at least in theory:

- Service discovery: Service A doesn’t need to discover the addresses of B and C, it can just let the control plane and proxy do that.

- Encryption: Encryption is now easier because all hosts are running proxies that are designed to handle this, and we don’t need to mess with the details of TLS in the services themselves.

- Complex routing: If we want to test a new variation of service B, for instance, we can configure the mesh to send 1% of traffic to the new instance and the rest to the older ones. If we discover a problem, we can reroute the traffic without redeploying the client code.

- Cross-fleet networking observability: Since all communication goes through the same layer, the mesh can expose a standardized set of metrics and logs for all inter-service links.

These benefits are particularly big when you’re in an environment with a diverse set of client and server implementations. Service A might be Ruby, B golang, and C Java. Sure, you could add mTLS, standardized metrics, etc. directly into each service, but you’re going to have to re-implement the same logic multiple times in multiple languages. Even if the services are written in the same language, they are probably not going to be using the same client and server implementations uniformly.

Implementations

Reviewing existing service mesh implementations is beyond the scope of this post. Instead, I’ll refer you to this site, which has a nice summary and seems up-to-date. As an alternative to adopting an off-the-shelf implementation, some companies simply take a “roll your own” approach using Envoy plus a custom-built control plane service; this is what we did at Stripe.

Why they’re hard

From the discussion above, it seems like service meshes are great. They make your infrastructure more secure, uniform, controllable, and observable. Everyone should be using them!!

Unfortunately, though, service meshes make life harder in a number of different ways.

Scope is N2

Let’s say you have N services and you want to update all of them in some way, for instance to replace a library with a newer version. Typically, this will involve O(N) updates and O(N) things that can go wrong. When rolling out a service mesh, however, you’re making O(N2) updates because you’re changing (and potentially breaking) how each pair of services communicates.

This means that, even with a small number of services, there are a lot of things that can go wrong (and will). Service A might be fine talking to B, and B might be fine talking to C, but the A to C link might occasionally time out for some weird reason that takes days to debug. If you’re in a company with dozens of services, the N2 effects can be huge- be prepared for a lot of work rolling things out and debugging.

More hops, more problems

In the non-service-mesh world, communication issues are typically the fault of either the client or server. If service A is getting HTTP 5XX responses from service B, you can look at the code and logs for B to understand why that might be happening.

In the service mesh world, on the other hand, these responses might be coming from B, the proxy on B’s host, or the proxy on A’s host. Now, instead of looking in one place, you have to look in three places. This means that the debugging process is slower and more tedious.

Encrypted traffic looks like binary junk

There are lots of great tools for inspecting unencrypted traffic. Personally,

I like running tcpdump -i any -A port [my service port] and watching requests

go back and forth when I’m trying to understand the traffic hitting a service. If

this traffic is encrypted, you can still do this, but all you’ll see is binary junk:

16:51:07.773675 IP lga15s43-in-f36.1e100.net.https > 192.168.0.10.56081: Flags [P.], seq 2713:3385, ack 537, win 261, options [nop,nop,TS val 2846442026 ecr 1037268748], length 672

..J..C..k.H...E....$..y..O...$...

......F...$o...........

..B*=.w.......7V.o.$(...wc.qk....2.ePyi\uXsTP..R..z.;S..

"iT....S...Ju.%..........%.....kZV0...EA9.W.NB.^.....f`

hV...i=8?...>8.".-..m.H.........y... .......?.G.$U<j...s.\>....;.....a......6@

[w.>SHQ.%...F....S..e ..f,..T(CA..U....x...../...8..(.j.....k..h.{.^...5n.4f.[....].x.....}

2.....Q..*.^..?.l...e$.~.]...j......P.....]....R..ZB....7..B9}e".....f.\..

AAV$m....z..m..........x..B.P.`0....k..E..S........$.......{.W..Most service meshes only use encryption on the proxy to proxy links and not on the proxy to service ones. But, these proxy to proxy links are often where a lot of problems happen, and not being able to easily inspect the details of each request on the wire makes debugging harder.

Certificate management is hard

In order to implement mTLS rigorously, you need to generate fine-grained certificates for all of the nodes in your mesh. Certificate management for individual hosts is hard enough, but it gets even messier when hosts are shared by multiple services and each one needs a distinct identity.

I spent many, many months at Stripe working on a “Service CA” to address this problem. We got things working in the end, but it required a lot of very careful design and relatively high-risk changes to components in the existing certificate provisioning flow.

Control plane is a single point of failure

The control plane is a critical component of a service mesh. It keeps all of the proxies updated with the latest service endpoints, routing rules, listener configs, etc. These updates may be happening frequently due to instances coming up and down, new services being added, and other changes happening in the environment. Depending on the sources of this information and the protocol used between the control plane and proxies, keeping all of the data fresh and accurate can be challenging.

In addition, the control plane can wreak havoc on your infrastructure if it’s misconfigured or gets confused about the state of the world.

A really scary type of incident, which I’ve seen a few times across multiple companies, is when the control plane thinks that all of the service instances have disappeared (for instance, because the source that it pulls these from is broken). It blissfully pushes out empty configs to all of the proxies, all inter-service communication stops, and your company is hard-down until the issue is fixed.

Proxies are complex

Many service meshes use Envoy as the underlying proxy. While powerful, Envoy is a beast; it has hundreds of knobs that can be tuned to affect its behavior.

The code is written in C++, which is not the easiest language to make changes in, and is prone to segfaults, leaks, and other types of memory issues if you’re not super careful. At Stripe, we occasionally observed crashes, which required a lot of work to understand and fix.

These issues aren’t unique to Envoy. Proxies in general are just prone to being complex, particularly when you’re trying to optimize performance and satisfy the many different use cases that people have for them.

Alternatives to service meshes

In some cases, you may be able to get the benefits of a service mesh with much less work.

For security

To prevent an unauthorized client from hitting a server, you can use firewall rules (called security groups in the AWS context) to lock down access. AWS and other cloud providers make it fairly straightforward to define these rules at the instance level and keep them updated.

If you’re in Kubernetes, you can also define service-level firewall rules via network policies.

If there is a particularly sensitive origin / destination pair, you can implement mTLS for just that pair in the client and server code or via a proxy on each side. Doing this as a one-off is going to be easier than implementing it for all service combinations in your infrastructure.

For load balancing and routing

If you’re running in a cloud environment, consider using hosted load balancers in front of your services (e.g., ALBs in AWS). These typically support target discovery, health checking, complex routing, standardized metrics, and other things that a service mesh also provides.

If you’re in Kubernetes, you can use services and other primitives to get the same kinds of features.

The path forward

If you’ve carefully evaluated the pros and cons and still decided to go forward with a service mesh, here are some tips to make the process a bit easier.

Plan carefully

Rolling out a service mesh is a really big project. It will require changes to nearly every service running in your infrastructure, and it can’t be released all at once.

Think carefully about the phases of the rollout. At Stripe, we started on the client side without encryption, then implemented the server side without encryption, then, finally, after that was stable, activated mTLS on a service-by-service basis. We were also very careful about the order in which services were updated within each phase. The optimal plan in your environment may be different depending on your risk profile and service topology.

Pad your estimates

Take your time estimates for the amount of engineer time required and multiply by 4. Seriously. Making updates and debugging networking issues in services you don’t fully understand is really time consuming. Moreover, you’ll discover weird use cases and requirements that you didn’t plan for and will need to incorporate into your design.

At Stripe, we originally thought that one person could roll out our service mesh in 3 quarters. In the end, it took over a year with 4 people on the team contributing. Because we hadn’t planned for that much work, we had to defer other projects that we had promised to do (e.g., rolling out Kubernetes more extensively), which caused some resentment among our users.

Make it easy to switch back and forth

Whenever a change is made (e.g., switching a service pair to the service mesh), keep the old path around for a while and make it easy to revert back. At Stripe, we had a dynamic, “feature flag” system we could use for this; other companies I’ve been at have had similar configuration mechanisms.

If there’s an urgent problem in the middle of the night, it’s a lot easier to revert by clicking a button in a UI than it is to revert the change in the code, wait for CI, and do a deploy.

Don’t roll your own

Please, please use an existing service mesh implementation if at all possible as opposed to rolling your own. Even if you can’t use an existing implementation directly, consider ripping out and reusing the pieces that can be adapted to your environment.

At Stripe, we built our control plane components completely from scratch. While it was a lot of fun personally, it took a long time to develop and there were a number of very tricky corner cases that popped up and led to serious production incidents along the way. It’s much safer to adopt service mesh components that have been written by domain experts and been extensively battle-tested outside your company.

Conclusion

Service meshes have a lot of benefits, but also a number of downsides that should be carefully considered before committing to a rollout. Thankfully, things should get better in the future as cloud providers include more service mesh features directly into their products and third-party solutions like Istio become more robust. In the meantime, though, be careful!