Migrating to Kubernetes, part 1: Moving on from the legacy service platform

Over the last few years, I’ve worked on Kubernetes migrations at several companies- Airbnb, Stripe, and, most recently, Segment (my current employer). In this post, I want to talk about why these migrations are done and what they involve from the platform standpoint.

Note that this post is the first of two in my “migrating to Kubernetes” series. Once you’re read this one, check out part 2 on why these migrations are hard and some tips for a smoother transition to Kubernetes.

Why migrate?

There’s lots of existing documentation about what Kubernetes is and how it works (e.g., this one), so I won’t cover those here. It is worth noting, however, the primary reasons that many companies decide to migrate to Kubernetes from their legacy platforms (discussed more in the next section):

- The ecosystem: A vast ecosystem of tools and apps has developed around Kubernetes over the last few years. By using Kubernetes internally, it’s easier to take advantage of the work that others have done, both in the infrastructure layer (e.g., for networking, service discovery, etc.) and in the applications that are being run on top.

- Vendor agnosticism: Kubernetes provides a layer of abstraction on top of whatever you’re using to provision individual machines and the associated infrastructure (networking, persistent disks, etc.). In theory, switching to Kubernetes makes it easier to do things like switch between cloud providers, although in practice this is still hard because of all the non-Kubernetes-related infrastructure you need to migrate as well.

- Easier, more self-service workload management: Kubernetes exposes a rich set of APIs and controllers for deploying applications, ensuring that they run reliably, and enabling developers to debug them when things go wrong. In theory, developers can take advantage of these features “out of the box”, without worrying about low-level machine details, writing lots of custom tooling, or depending on a separate “infra” team in the organization to set things up.

Legacy service platforms

The process for migrating to Kubernetes depends a lot on what you’re migrating from. This includes not just whatever is being used to build and deploy applications, but also the wider set of infrastructure and tooling used for managing application environments in production.

By analogy to the PaaS products that are offered by some cloud providers, I’ll call this pre-Kubernetes “bundle of stuff” a legacy service platform or LeSP for short. Normally I hate the term “platform” since it’s so overused (seems like it’s super trendy at the moment for companies to be building “platforms” instead of “products”), but in this case I think it’s actually appropriate- the LeSP is literally a base on which applications in an organization are created and run.

The exact details of the LeSP will vary a lot from company to company. Typically, though, they have some common characteristics.

It’s about machines

In a LeSP, the main unit of compute is a machine, either a virtual machine (VM) like one provided by AWS EC2 or a physical box sitting in a data center somewhere.

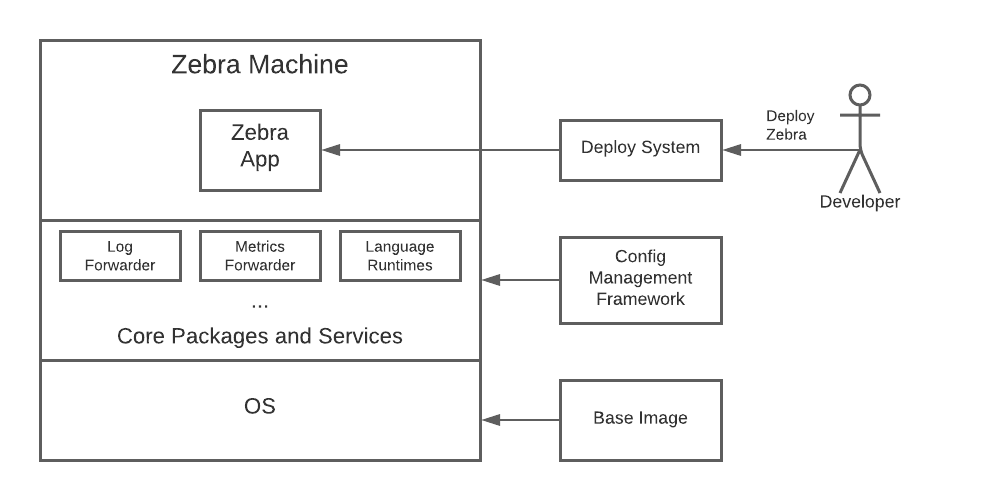

Machines are provisioned from a base image that includes the operating system and other, low-level software. There is then a configuration management process, typically orchestrated by a framework like Chef or Puppet, that installs the higher-level tools and systems needed to run applications on the box- these might include language runtimes for things like Python and Ruby, log and metrics collectors, performance monitoring tools, and company-specific automation scripts, among other things.

Applications and identities

Each machine is configured and provisioned for a specific application. So, if you have ten different services running in production, you’ll typically have ten different machine variants, each running in a separate pool. The “zebra” service will have “zebra machines” that contain the specific things it needs to run (maybe a JRE), the “cheetah” service will have “cheetah machines” that contain what it needs (maybe a Ruby interpreter and an Nginx process), and so forth.

Identity, as it pertains to networking and authentication, is at the granularity of a machine. All processes running on the same host use the same IP address(es), the same cloud role, the same x509 certificates, etc. So, the “zebra machines” will run with the “zebra” role, use a “zebra” certificate, live in a “zebra” network security group, etc.

Deploys

The primary application processes on each instance are typically created and updated by a higher-level deploy system. So, for instance, if a developer wants to update the “zebra” service in production from version 1234 to version 1235, they would give the deploy system the new version (or this would be automatically detected), and then the latter system would handle getting onto each of the “zebra machines”, pulling down an updated artifact, extracting out whatever binaries, scripts, and configs the application needs to run the new version, and restarting the app.

These deploy systems are typically pretty complicated because they need to support all of the various rules, workflows, and infrastructure quirks specific to each organization. A few, like Netflix’s Spinnaker, have been open-sourced, but many companies still end up building their own because of the amount of customization required.

Kubernetes service platforms

When you migrate to Kubernetes, you’re replacing the LeSP with a new, Kubernetes-based service platform. Following the same naming style, let’s call this thing a Kubernetes service platform or KuSP for short.

KuSPs have a few big differences from LeSPs, which are described in the sections below.

It’s about containers

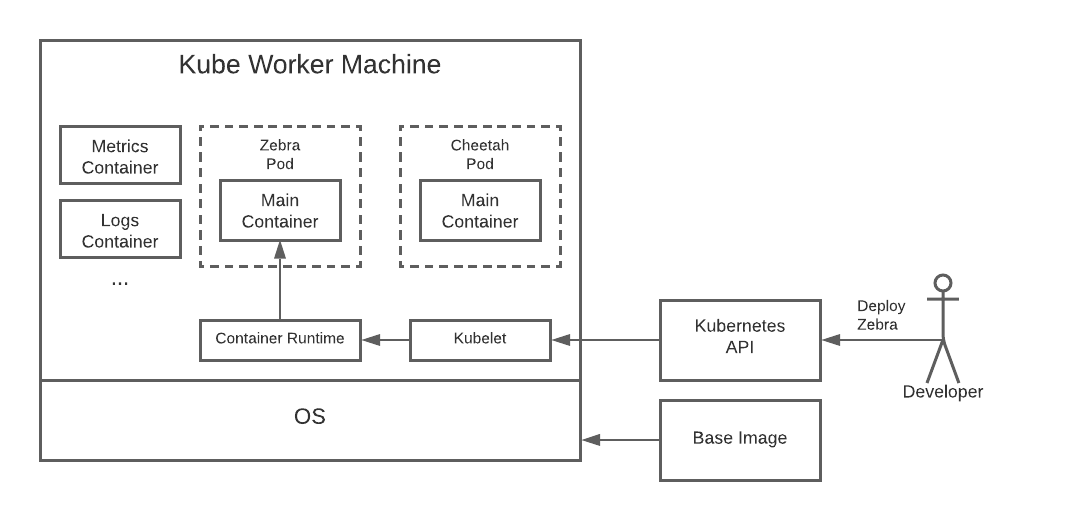

In the KuSP, as opposed to the LeSP, the main unit of compute is a container, not a machine. At a high level, a container is just a semi-isolated process. Each container runs from an image, which is effectively a layered, read-only bundle that contains the binaries, tools, and configs needed to create the environment in which the container runs.

Containers run in machines, so you still need to provision them, but the configuration for these machines can be simpler and more generic. The main requirement is to install a container runtime such as Docker. Once the latter is in place, you can use it to run containers for your applications and various helper services (for logs, metrics, networking, etc.). You can still use Chef or Puppet if you want to, but these are less important because much of the heavy lifting is now done in the higher-level container and orchestration layers.

Applications and identities

In a container-based service platform, applications are less coupled to specific machine variants. The “zebra” service can still have its own, “zebra machine” pool, but this is less necessary than before because most of the service-specific components can be baked into the service image as opposed to being installed on the instances on which the container runs.

Identity also moves from the machine to the container layer. Each container can now have its own IP address, x509 certificate, cloud service role, etc. independent of the identity of the host that it’s running on. This isn’t a drop-dead requirement (containers can use the host network, for instance), but it’s considered best practice from a security and isolation standpoint to enforce this separation.

Orchestration via Kubernetes

Containers by themselves are fairly low-level and specific to individual machines. Kubernetes adds yet another level of abstraction on top of containers that orchestrates changes across containers in a cluster of machines. With Kubernetes, applications are updated by changing the associated resources in the Kubernetes API. The Kubernetes control plane then figures out which containers on which instances need to be changed, and a special agent on each machine, the kubelet, actually carries out the updates.

Although it’s still possible to have a custom deploy system for managing workflows and such, this system ends up delegating most of the low-level details of each update to the Kubernetes API.

Kubernetes doesn’t just handle image updates for individual containers. It provides a ton of other functionality as well including bundling containers together as a unit (i.e. a pod), configuring container networking, mounting container disk volumes, storing and exposing application secrets (e.g., DB passwords), monitoring container health, restarting failed containers, exposing APIs for viewing logs, allowing developers to “exec” into containers for debugging purposes, etc.

Not all of these things are required. You may, for instance, be able to keep using your LeSP secrets system instead of migrating to Kubernetes secrets. But, there are a lot of choices to be made here, and using non-standard or non-Kubernetes-aware solutions here might require some extra work.

Conclusion

Migrating to Kubernetes involves moving from a machine-based, legacy service platform (LeSP) to a shiny, new, container-based one (the KuSP). This transition doesn’t just change how processes are executed at a low-level, but also affects higher-level things like application identity and deploys.

The next post in this series describes why the migration is hard and what can be done to make it a bit less painful.