Cleaner go code with golines

Last year, with the generous support of my employer, I open-sourced golines, a tool that automatically shortens long lines in go code. At the time, I was busy with other work so I never got a chance to write about it beyond the basic documentation in the project README. In this post, I want to explain more about why I developed the tool and how it works.

The problem

The standard tooling for the go programming language includes

gofmt, a very solid code formatting utility. gofmt

automatically applies the standard go rules for indents and spacing, for example converting this

mess:

func myFunc (s string, t string) ( string, error) {

v := fmt.Sprintf( "Combined: %s %s", s, t )

return v, nil

}into a logically equivalent but much prettier variant:

func myFunc(s string, t string) (string, error) {

v := fmt.Sprintf("Combined: %s %s", s, t)

return v, nil

}Unfortunately, this tool and the others that extend it

(e.g., goimports) don’t do anything about

long lines. gofmt will happily leave the following code as-is:

func myFunc2(longArg1 string, longArg2 string, longArg3 string, longArg4 string, longArg5 string, longArg6 string) string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%v", map[string]string{"longArg1": longArg1, "longArg2": longArg2, "longArg3": longArg3, "longArg4": longArg4, "longArg5": longArg5, "longArg6": longArg6})

}Personally, I find it much more readable in cases like this to split out the function arguments and map key-value pairs onto separate lines:

func myFunc2(

longArg1 string,

longArg2 string,

longArg3 string,

longArg4 string,

longArg5 string,

longArg6 string,

) string {

return fmt.Sprintf(

"%v",

map[string]string{

"longArg1": longArg1,

"longArg2": longArg2,

"longArg3": longArg3,

"longArg4": longArg4,

"longArg5": longArg5,

"longArg6": longArg6,

},

)

}I like go, but for years it bothered me that there was no automatic way of applying the above types of cleanups. When going into a new codebase, I would manually shorten the worst offenders, which was fine for small projects but got tedious in large ones that had accumulated years of long-line commits. I decided to make this process easier by writing my own tool!

Aside: Who cares?

Although many support this crusade to shorten long lines, I’ve definitely gotten some skepticism over the years about both my manual fixes and attempts to write an automated tool. The main arguments (and my responses) have included the following:

You can just wrap lines in whatever code editor you’re using!

Yes, that’s true, but not everyone uses the same editor and not all editors handle wrapping gracefully. In addition, many online reviewing tools don’t wrap lines, so this doesn’t help when I’m trying to understand your 200 character-wide function declarations in Github.

Line length is a matter of preference. We shouldn’t impose a constraint that others may disagree with.

True, but so is spaces vs. tabs, whether to put the opening { on the same line as a function

definition or the next one, and many other style disputes that gofmt and other tools take

very definitive stands on. You have to impose some standards, otherwise each file in your repo

will look completely different based on who last edited it.

I find having all function arguments, all map key-value pairs, etc. on a single line easier to read.

Really? Well, maybe this could be valid in some cases. However, it’s generally easier to scan vertical lists than horizontal ones. This is why we use bullet points so much in presentation slides. Although a horizontal list might be ok in some cases, a vertical orientation should never make it significantly worse and in many cases be an improvement.

First attempt: Regular expressions

My first attempt at automating the line shortening process was to write a script that used regular expressions. The basic algorithm was:

- Go through each line in the file

- If the line is already shorter than the threshold (e.g., 100 columns), leave it as-is and continue to the next one

- Otherwise, loop through a set of pre-defined, “splitter” regular expressions

- If the line matches one of these, insert newlines according to some associated, pre-defined logic, then continue to the next line

- After reaching the end of the file, run

gofmtto fix the spacing issues created by (4)

I then went about creating the regular expressions to use. It started off relatively easy; for instance, to pick up the case of a long line with a function call, I used something like:

^\s*\w+\((\w+)(,[ ]?\w+)*\)$

That will match hello(arg1, arg2,arg3). We can then have some logic that

inserts newlines and a final comma in the appropriate places:

hello(\narg1,\n arg2,\narg3,\n). The end result, before running the final

gofmt, thus renders as:

hello(

arg1,

arg2,

arg3,

)gofmt then fixes the indents on each line so that it actually looks nice and matches the

surrounding code.

I then made similar regular expressions and fixing logic for a few other common cases, including long function declarations and simple key-value maps.

The initial version worked decently well, fixing around 70% of the long lines in an old go repo at my then employer. Next, I went through and improved the regular expressions to fill in some of the gaps. In the example above, for instance, what if an argument has quotes around it? What if someone has already done a single split in the middle, but one or both of the segments is still too long? There are many, many cases to cover. After a while, the regular expressions got so big that I had to split them up into smaller clauses and use text templating to put them together.

Even with multiple iterations, it was difficult to match more than 80% or so of the long lines. The hardest cases to cover involved nesting. In the above example, for instance, each function argument could itself be a function call, and those arguments could include function calls, and so forth. I would try something that seemed promising, only to hit a case that would cause the regular expression matcher to get stuck in a catastrophic backtracking loop.

In the end, I just gave up. I’m not a regular expression expert, so maybe there could have been some way to rewrite my expressions to make them more efficient, but even if I did that, it seemed like fixing all of the corner cases would be a never-ending game of whack-a-mole.

Second attempt: Use ASTs

The theory

Ultimately, the grammar of the go language is just too complex to be “interpreted” by simple regular expressions. The go compiler takes a different approach- it uses a parser to create an abstract syntax tree (AST) representation of the code. I never took a class on compilers, so I’ll leave the theoretical details to the experts. The main idea, however, is to convert code from a linear sequence of bytes into a tree that can be used for “understanding” what the code actually represents. The latter representation can then be transformed into lower-level machine code.

The go compiler, for instance, converts this code:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

v := "hello"

fmt.Printf("%v", map[string]string{"key1": fmt.Sprintf("%s-%d", v, 4)})

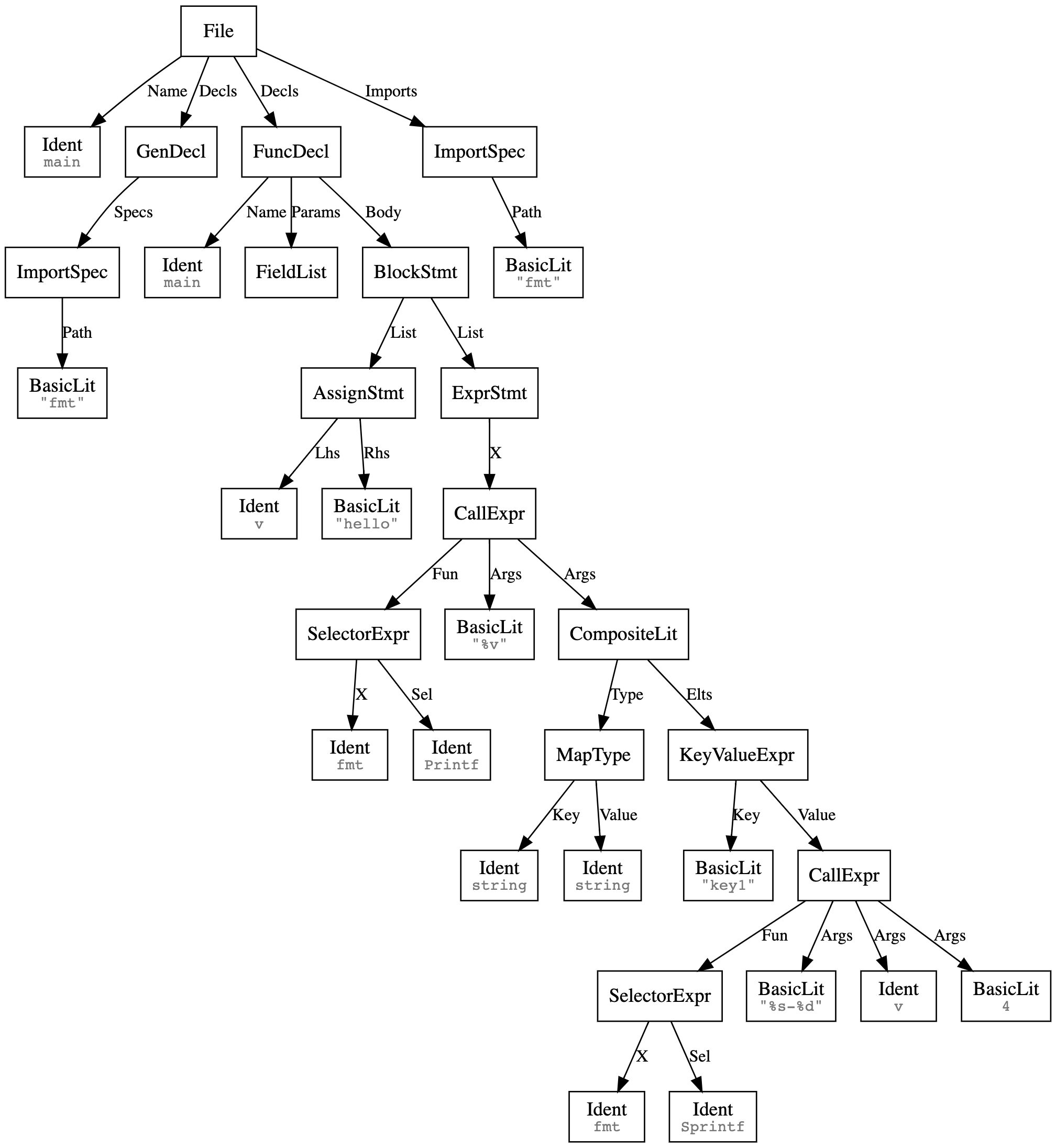

}into the following AST:

It looks scary at first glance, but if you walk through from the top and follow along in the code, it makes intuitive sense. The great thing about ASTs is that they automatically handle the nesting and splitting that was so hard when using regular expressions. Go also exposes the AST generation process and structs in the standard library, so it’s fairly easy to create representations like the one above.

Now, in theory, we can modify the regular-expression-based shortening algorithm above to work on an

AST instead of a sequence of lines. Instead of looping through lines, we can do a depth-first

traversal of the nodes. If a node is on a long line, we can insert newlines between its children

and/or recursively apply our shortening on them. The exact logic here depends on the node

type, but in the case of a CallExpression (i.e., a function call) for instance, we would

insert newlines between each of the children Args. Then, at the end, we can convert the AST

back to code and run gofmt to fix the spacing on each line.

The implementation

This is all great, but there’s one significant problem- ASTs are abstract. In general, they’re intended for compilation, not code formatting, so details like spacing and newlines might be incomplete. In the go case specifically, it’s hard to tell what the length of a line is just by looking at the AST nodes that were generated from that line.

As I dug into the AST-based approach, I realized that this was going to be a significant blocker- if we didn’t know line lengths, it would be impossible to figure out which AST nodes to modify. I needed some way to link the state of the original code (i.e., that a particular line is too long) to its AST representation, but without modifying the logic of the code itself.

After some trial-and-error, I figured out that comments could be one way to make this link. In particular, the tool could first add comments to the long lines in the code, then generate the AST. We could then check each node to see whether it had one of these “line too long” comments to determine whether we should try to split it out onto multiple lines.

The golang AST does include comments, but unfortunately they’re not directly linked to other nodes

in the AST. Thankfully, however, there’s a third-party AST generator,

dave/dst, that does maintain these links. By using this, I could

mark the long lines, generate the AST, and then traverse the graph and insert newlines in the

appropriate places to break up the long lines. The “control comments” could then be scrubbed

at the end so they wouldn’t appear in the final formatted output.

Once I got the initial skeleton in place, the rest of the work involved figuring out how

to split each node type. In most cases, it was fairly straightforward- function declarations

and calls, for instance, can be split between the arguments. It got tricker, however,

when dealing with cases where the top-level node is not the one that you actually want

to shorten. If you’re shortening an assignment, for instance x := myFunc(...), then you

really want to shorten the right-hand-side, which is in a lower-level node. In these cases,

you need to “push” the shortening work down recursively.

From testing to release

After lots of trial-and-error, I got the tool, which I decided to call golines, working for all

of the fixtures that I could generate myself. The next step was to run it on real code to make

sure that it (1) wouldn’t crash, (2) would make progress at a reasonable speed, and (3) would

actually shorten long lines in a reasonable way.

I started with some of the smaller go repos inside Segment, and worked my way up to large, open-source projects like Kubernetes. Along the way, I filled in the various AST node types that were omitted in my first pass and also used pprof to discover and alleviate the performance bottlenecks.

In the end, I got to a point where I felt fairly confident about the quality of the tool and

kicked off our internal process for open-sourcing. A week later, golines was out in the wild and

available for general use!

Conclusion

If you’re annoyed by long go lines as much as I am, please give

golines a try. And, if you notice any problems or

have enhancement suggestions, file an issue in the repo. External contributions are welcome as well.